Lecture 3

CONSEQUENTIALISM IN GENERAL

All versions of consequentialism postulate that the moral status of a given action (i.e., whether this action is permissible or not, right or wrong, optional, obligatory or forbidden, etc.) depends solely on the good and bad consequences of this action (benefits and harms).

Consequentialists must address four different issues:

-

What counts as good consequences (benefits) and what counts as bad consequences (harms)? What kinds of things and situation are intrinsically good and bad?

-

Are some values more important than others and always (or typically) take precedent over other values? (E.g., see the debate between the quantitative hedonism (Bentham) and qualitative hedonism (Mill).)

-

Do harms and benefits of someone (some beings) count for more or less than harms and benefits of other beings? (E.g., do interests of people belonging to some race count for more than interests of other beings? Do animal harms matter?)

-

Is it obligatory to maximize good consequences, minimize bad consequences, bring about the best ballance of good and bad consequences, satisfise (i.e., come close enough to the best outcome) or what?

Depending on how those questions are answered, we can develop different vesions of consequentialism. For example, some philosophers argue that only pleasure is intrinsically good (good in itself) and only pain is intrinsically bad (bad in itself); others argue that there are many different things that are good or bad in themselves. Also, some philosophers argue that we ought to bring about the best balance of utility (or the best difference between benefits and harms) while others argue that satisficing is good enough. (The idea is that, if we come close enough to the maximum, our action is right.) Finally, there are views maintaining that the interests of some beings count less than interests of other beings (racism and sexism are examples) and there are views maintaining that similar interests count similarly.

By contrast, non-consequentialist theories postulate that he moral status of a given action depends on factors othher than the consequences of this action. Some of these theories postulate that morally right actions are just those that fulfill our duties. The Greek term "deon" is a counterpart of the English term "duty". Thus, theories based on the idea of fulfilling one's duty are versions of deontology. Other versions of non-consequentialism may postulate that we ought to respect moral rights, that we ought to act in virtuous way, and so on, and so forth. Yet other versions of non-consequentialism postulate that right actions are what a virtuous person would do (that's virtue ethics in Aristotelian sense).

TWO KINDS OF EGOISM: PSYCHOLOGICAL EGOISM VS. ETHICAL EGOISM

Psychological Egoism (PSE): As a matter of fact, everyone always tries to act (is motivated to act) in his or her own interest.

Ethical Egoism (EE): Every person ought to act in a way that is in the interest of this person. That is, an act is morally right if and only if it is in the agent's interest.

Psychological egoism is not an ethical theory (and not a normative theory at all). It describes how we act but does not tell us how we ought to act. By contrast, Ethical Egoism is a normative ethics theory.

If Psychological Egoism is true, however, then there are major implications for ethical norms. PSE implies that we never act altruistically, i.e., to advance the interests of others for their own sake (and not just for our sake). If we this is true and if we cannot overcome this selfish motivation, we could not develop an ethical theory requiring of us to do things for others. For such a theory would require of us to do impossible. So, it would follow that all moral requirements would have to be consistent with the thesis that we ought to act in a selfish way.

IS PSYCHOLOGICAL EGOISM TRUE?

Rachels gives several examples of people who acted altruistically (e.g., Wallenberg, Allsop, Kravinsky and others, see p. 64ff). We know of other examples of people who commit acts of extreme self-sacrifice; e.g., a woman risks her life by jumping in a river to save a total stranger or a soldier throws his body on a live grenade to help his comrades. Also, parents and family members often make sacrifices that are hard to explained in terms of self-interest. So, psychological egoism seems false. Can it be defended?

Argument 1 (We always do what we want to do)

1. Whenever we act, we are motivated by our desires and wants.

2. If we are motivated by our desires, then we are motivated by self-interest.

3. So, whenever we act, we are always motivated by self interest.

______

4. Therefore, altruism is not possible

Two Replies to Argument 1

Reply #1: There are acts that we do not want (desire) to do, but feel we ought to do. E.g., we join an army (and go to war) because we think it's our duty. So, it seems, sometimes we are motivated by something else than our desires. For example, we may be motivated by a sense of duty. It would follow that we are not always motivated by our self-interest.

A defender of psychological egoism might continue along the following lines: but, in this case, we still desire to fulfill a duty. So we are motivated by our desires. So, see reply #2.

Reply #2: Being motivated by our desires is not the same as acting out of self-interest. That is, we have to distinguish between questions about whose desire is it (e.g., it is my desire or my want) and what do we desire (i.e., what the content of our desires is).

The crucial distinction here is the distinction between self-regarding desires (wants, motives, reasons, and so on) and other-regarding wants.

I want to eat healthy healthy because it is good for me.

Many people have a desire that certain thing happen to other people or animals. For example, someone may eat vegetarian-healthy because it is good for animals and environment (in addition to health reasons). They may act on their desires (i.e., the desires they happen to have). But those desires may concern others.

People who act in altruistic way, like Wallenberg or Schindler had desires to help others. We may say that his desire was others-regarding (as opposed to self regarding). So, these people are not selfish or egoistical.

Argument 2 (we do what makes us feel good)

1. When we seem to act altruistically, we feel good.

2. The good feeling we get is the real motivation behind altruistic acts.

3. Therefore, we never really act altruistically (true altruism is impossible).

Three replies to argument 2

Reply #1: The psychological egoists’ account of human psychology is implausible.We do not always feel good when we do things for others.

Reply #2: Even if I know that something will be a result of my action, it does not follow that I act to bring about this results. (E.g., in the Siamese twins case in Chapter 1, doctors knew that one twin will die; but they did not try to bring about this result. Similarly, I know that if I eat ice-cream I will put on weight; but I do not eat ice-cream to put on weight.)

Reply #3: The fact that one might have a self-interested motive does not exclude other and perhaps more important motives that are benevolent.

In general: The most important distinction here is the distinction between self-regarding and other-regarding reasons, motives, wants, desires, etc. The object of our desires is frequently not a feeling of satisfaction but rather that something happens in the world and that others are affected in a certain way. These are other (rather than self-) regarding reasons.

But what if all of this is but instinct. Or, are animals selfish?

Someone may argue that animals are selfish to the core. If animals are selfish, and we are just animals, then we are selfish, too. But there are numerous studies suggesting that animals show kindness and empathy and have some sense of fairness and "morality". Check out, for example some of these videos:

- Monkeys show cooperation and fainess [ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BYJf2xSONc&ebc ]

- Monkey have a sense of fairness: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1wmUyOyM0m0 ]

- Dogs have a sense of fairness, too [ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qTiGlCxrIA ].

- Empathy in rats [ https://youtu.be/nyolz2Qf1ms ]

IS ETHICAL EGOISM TRUE?

Individual Ethical Egoism: Everyone ought to pursue my best interest.

This theory is indefensible. For example, it fails to satisfy the requirement of impartiality. Thus, it's a false ethical theory (or not an ethical theory at all).

(Universal) Ethical Egoism (EE): For every person, her act, A, is morally right if and only if A is in the interest of this person. (That is, An act, A, is morally right if and only if it is in the agent's interest.)

Ayn Rand and Ethical Egoism:

There are philosophers who proposed, and attempted to defend, a thesis similar to (EE). For example, according to (recently popular) Ayn Rand (1905-1982):

The ethics of altruism has created the image of the brute . . . in order to make men accept two inhuman tenets: (a) that any concern with one's own interests is evil, regardless of what these interests might be, and (b) that the brute's activities are in fact to one's own interest (which altruism enjoins man to renounce for the sake of his neighbors) . . .

Altruism declares that any action taken for the benefit of others is good, and any action taken for one's own benefit is evil. Thus the beneficiary of an action is the only criterion of moral value-and so long as that beneficiary is anybody other than oneself, anything goes . . .

Altruism permits no concept of a self-respecting. The Objectivist ethics (of egoism) holds that the actor must always be the beneficiary of his action and that man must act for his own rational self-interest. (Ayn Rand, "The Virtue of Selfishness" (broken link))

In her writings, Ayn Rand creates a sharp contrast, or a dichotomy, between the thesis of altruism (that we always ought to act for others) and her own version of ethical egoism that she called "the objectivist ethics" (because, for example, she rejects all religious assumptions). According to Rand, the altruistic ethics is inhuman and indefensible. She seems to think that egoism is the only alternative to altruism. Hence, she seems to think that her argument supports ethical egoism

Ayn Rand’s Argument for EE

1. Either Ethical Altruism (EA) is true or Ethical Egoism (EE) is true.

2. If Ethical Altruism is true, then one ought to sacrifice oneself for others.

3. Noone ought to sacrifice oneself for others.

4. So, Ethical Altruism is not true. (from 2 & 3)

________

5. Therefore, Ethical Egoism is true. (from 1 & 4)

Problem with Rand’s Argument: In her attempt to defend Ethical Egoism, Rand presents us with a false dichotomy; namely, that either ethical egoism or ethical altruism is true. There are other options she has not refuted.

False dichotomy arises when the premise of an argument presents us with a choice between two alternatives and assumes that they are exhaustive or exclusive or both, when in fact they are not.

Arguments that altruistic behavior is self-defeating

These arguments start with an assumption that we are best judges about what our needs and interests are and also we are best at attending to our own needs and interests. Then they continue with the claims that looking for others is an offensive intrusion into their privacy and that it is degrading to meddle in other people’s lives. Furthermore, if each of us attends only to our own interests then all of us will benefit and the society will be more harmonious.

1) We ought to do whatever will best promote everyone's interests.

2) The best way to promote everyone's interests is for each of us to adopt the policy of pursuing our own interests exclusively.

___

Therefore, 3) each of us should adopt the policy of pursuing our own interests exclusively.

Problems:

Problem 1:

"If we accept this line of reasoning, then we are not being ethical egoists. Even though we might end up behaving like egoists, our ultimate principle is one of beneficence -- we are doing what we think will help everyone, not merely what we think will benefit ourselves.” (Rachels, p.71)

Problem 2:

Furthermore, it is not true that each of us is best in attending to our own interest. Consider, for example, small children, people who are mentally ill, or brain-washed.

Problem 3:

Finally, it's not true that when each of us is pursuing our own interests it is also best for everyone. (On this topic, see chapter 6:2 on the Prisoner's Dilemma.)

Ethical Egoism & the Common Sense Morality: Ethical Egoism is not a revisionist doctrine at all, but compatible with common sense morality. After all, don’t we have strong self-interested reasons not to harm others, lie, cheat, keep our promises? Perhaps Ethical Egoism is the foundation of common sense social morality.

Objection #1: It is not always to one’s advantage to follow the rule of common sense morality (e.g. do not lie, do not steal, do not harm others, and take care of children). In fact, sometimes rules of common sense morality are in conflict with EE. (E.g., suppose that a rapist can get away with a rape, a tyrant can get away with his tyranical ways, or a thef can get away with stealing, etc. EE implies that they should break rules of common-sense morality and rape, oppress their subjects, or steal.)

Objection #2: The primary object of our concern need not always be ourselves. Perhaps a good reason to help a starving child is because the child will die without our help.

A Deep Problem With Ethical Egoism -- Egoism and Impartiality

Rachels argues that egoism violates the Principle of Impartiality. In his version of this principle

(Rachels on Impartiality): We ought to treat people similarly, taking interests of each into consideration, unless there are some relevant differences between them.

Because EE violates the Principle of Impartiality, it is like racism and sexism. A racist violates the principle of equal treatment by arbitrarily giving preferential treatment to members of his or her own race. A sexist violates the principle of equal treatment by arbitrarily giving preferential treatment to members of his or her own race.The Ethical Egoist violates this principle by arbitrarily giving preferential treatment to him or herself.

"We should care about the interests of other people for the same reason we care about our own interests, for the needs and desires are comparable to our own" (Rachels, p. 78)

An even "Deeper" problem with Ethical Egoism (Egoism and "The Prisoner's Dilemma" and the importance of rules) (see chapter 6.2)

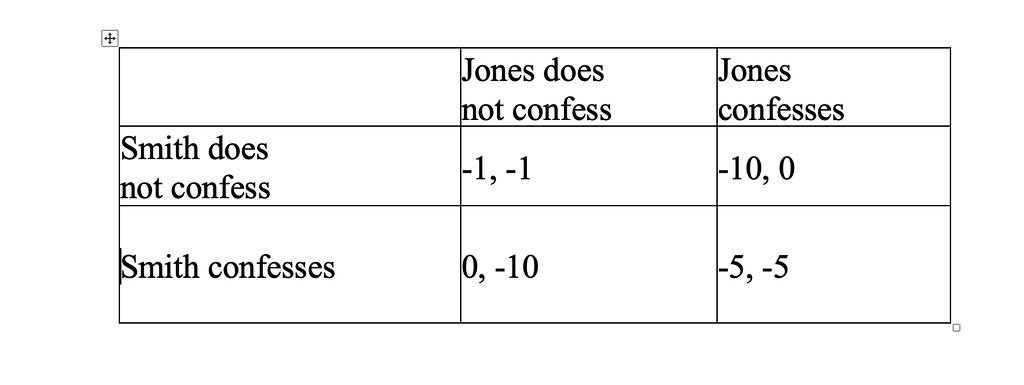

Many real life situations (especially situations we encounter when we pursue economic activities) have a structure of "the prisoner's dilemma". Here is a classic version of such a dilemma. Two people, Smith and Jones, are apprehended for minor violations by a tyrannical dictator. The dictator has enough to keep each of them in jail for 1 year. He knows, but cannot prove it, that each of them is involved in the movement intending to overthrown the tyrant. Thus, each of them is offered the following deal:

CONDITIONS OF "THE DEAL":

0) We have enough to keep each of you in prison for 1 year. If you do nothing at all, each of you will spend 1 year in prison. Utilities: -1 for you, and -1 for the other.

1) If you confess and provide evidence allowing the state to convict the other, you will go free and the other will spend 10 years in prison. Utilities: O for you, -10 for the other.

2) If you do not confess but the other prisoner does, you will spent 10 years in prison, while the other prisoner will go free. Utilities: -10 for you, 0 for the other.

3) If each of you confesses, each of you will spend 5 years in prison (your confession will be use as a mitigating cicumstance). Utilities, - 5 for you, and -5 for the other.

4) The other guy is offered exactly the same deal.

Here is a matrix of utilities representing "the deal":

Let us now assume that both Smith and Jones are pure unconstrained ethical egoists. Under these conditions, each of them should confess. This is the case because Smith is better off confessing, no mater what Jones does. For, if Jones does not confess, Smith will go free rather than spending 1 years in prison. While, if Jones confesses, then Smith will spend 5 years in prison, rather than 10. In other words, from the point of view of Smith, confessing is the dominant strategy; i.e., the strategy that guarantees the best outcome for him no matter what Jones does. The same applies to Jones. That is, confessing is the dominant strategy for him, too. So, the unconstrained Ethical Egoism would lead each of them to confess. But this will result in each of them achieving only the 2nd best option (5 years in prison rather than only 1 year, if neither were to confess). In other words, it seems like the unconstrained egoism is self defeating. Namely, it does not assure that the agent will do as well as he could have done in these circumstances, if both agents abandoned the unconstrained egoism and decided to cooperate.

Possible solutions to "the Prisoner's Dilemma": Each solution requires agents to reject the unconstrained egoism. It implies that the agents ought to cooperate with each other and abstain from confessing and sending the other to a longer jail term.

A) Suppose the agents agree that both of them will not confess. Since they are egoists, how can they guarantee that they will keep this agreement? One possibility is to choose someone as an "enforcer" of their agreement. The enforcer will impose very stiff penalties on the party that violates their agreement. For example, an enforcer may execute the party that violates his end of the bargain, which would be much worse than even 10 years in prison. After the agreement is at place, it would be in each prisoner self-interest to stick with the agreement. That is, each of them would have a reason not to act like a pure unconstrained egoist.

B) The agents may reject egoism as a matter of principle. Instead, they may decide to act on a different principle. That is, they may adopt a principle that requires a more benevolent behavior, the behavior that is beneficial for a society or a group as a whole (rather than acting purely in self interest). Now, notice that in this case, cooperation (i.e., not-confessing) is the most beneficial outcome for the group. The utility of this outcome is -2 ( = -1 & -1 for each of them) rather than -10 (the group utility of every other option).

Conclusion: The solution A) is accepted by some versions of "Contract Theory" (see chapter 6). The central idea for theories of this sort is to postulate that morality is a system of rules that rational egoists would adopt provided that other people in their society also adopt, and live by, these rules. A bit more on this topic below.

The solution B) rejects the most basic assumption of ethical egoism that, at the most basic level, we ought to act like egoists and that we just have to somehow constrain our selfish tendencies. It postulates instead that, at the most basic level, we ought to do what benefits the society as a whole. Utilitarianism, a theory discussed in Chapters 7-8, is this sort of theory.

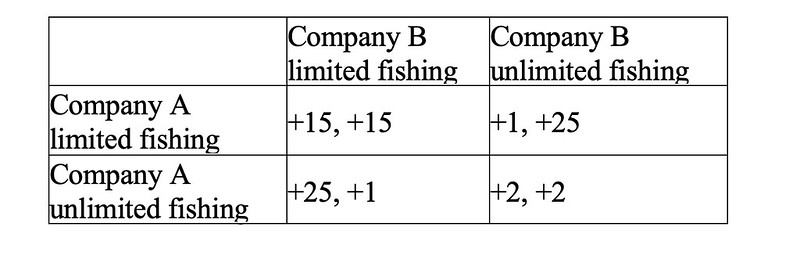

Another Example of the "Prisoner's Dilemma"

Consider a situation involving two companies, each fishing for shrimp in the same area of the Mexican Gulf. They may each try to fish as much as they can (unconstrained fishing). One of them may decide to put some limits on their fishing. Or both of the may involve into limited fishing, accepting some quota and limitations on how much shrim they can fish. Imagine that the following are the facts of the situations, from the point of view of each company.

1) I put some significan limits on my fishing and so will they; consequently, each of us will make a hefty profit. (Utilities: +15 for me, +15 for the other).

2) I engage into an unlimited fishing while they do not; consequently, I will make a much better profit and they will make barely any profit at all. (Utilities: +25 for me, +1 for the other.)

3) Each of us fishes without any limitations; consequently, we will overfish, deplet shrimp in our area, and will not make a very good profit. (Utilities, +2 for me, and +2 for the other.)

Here is a matrix of utilities representing this situation:

Let us now assume that both A and B are pure unconstrained ethical egoists. Under these conditions, each of them should engage in the unlimited fishing. This is the case because unlimited fishing is the dominant strategy for each of them. That is, no matter what other do, it is best for each company to fish as much as possible (+25 > +15; +2 > +1). But, if each of them acts on this strategy, they will overfish. In effect, each of them will be worse off that they could have been otherwise (+2 < +15). So, if they want to flourish and not just survive, they have to cooperate.

So, let's suppose they agree to cooperate. But, on the assumption they are purely selfish, they would have no reason to obey this agreement. So, they need to make sure that they have an incentive to act by the rules they have accepted.

One way to do it is to "constrain" the market and their activity. That is, they may delegate some of their powers to an "enforcer" who will impose very stiff penalties on the party that violates their agreement. For example, an enforcer may impose very stiff monetary penalties on the party that breaks the rules, or may even prohibit this company to fish, or may sent its executives to jail, and so on and so forth. After all of this is at place, each company would have a very strong inscentive to act according to the rules and limitations they have accepted.

But who can play the role of such an enforcer. The government, represented by its agencies, seems to be uniquely positioned to enforced the rules and regulations. If all of this is correct, we have an explanation how certain laws and regulations come into being and why they are justified.

Philosophers in the camp of so called "Social Contract Theory" (see chapter 6) tell a similar story when they explai the origins of morality and when they offer justification for moral rules. The central idea for their theories is that accepting and internalizing moral rules is mutually beneficial, provided that the great majority of people in our society also accept and internalize these rules. As David Gauther expresses this idea, we should "bargain our way into morality" (p. 88).

The question is what or who would play a role of an enforcer? Typical solutions postulate two ideas: First, society as a whole may "punish" those who violate moral rules that are the results of agreement. For example, we might be called names (such as a liar, a wrongdoer, a wicked or evil person, an ass-hat, and so on and so forth). That's the idea of so called "external sanctions". Another (and not exclusive) idea is to postulate that, once these rules are internalized, our own consciousness would "punish" us from within when we violate the rules. For example, we will feel guilty or we will have feelings of shame when we violate these rules. That's the idea of so called "internal sanctions".

Whether theories of these sort are completely workable is an open question. I will mention here but two kinds of problems contractarianism encounters:

A) It is not clear why we should start with the assumption that we are (psychological) egoists. We have seen several problems with this assumption. Very likely, a great majority of people are not tcompletely selfish. Frequently we act from quite altruistic and benevolent motives. But non-egoists would agree to very different rules than selfish contractarians. They would agree to follow some rules even when it is not beneficial to them to follow them. So, it's not really clear what are the implications of "contractarian" approach. It's not clear what rules rational contractarians would accept. (I am assuming that, at least sometimes, altruistic and beneficial motives are rational.)

B) There are several kinds of beings who cannot bargain with us. Thus, they cannot enter into a mutually beneficial (or any other) contract with us. Among others, think about human infants, non-human animals, future generations, and even very oppressed groups of people who have no skills or political means to enter into any contract. So, why should we include them into the sphere of morality, if we are egoists? It is not clear at all how (completely selfish) contractarians might respond to these problems.

Contractarian theory is discussed more fully in chapter 6.